September 16, 2024

By: Brionna Benedetti, CPC, CRC

Download the full guide: CHPA 2024 Mental Health and Suicide Awareness Sept Newsletter

What is Suicide?

Suicide is a major public health crisis and one of the leading causes of death that affects people of all ages. The CDC defines suicide as “death caused by injuring oneself with the intent to die”, while a suicide attempt as “when someone harms themselves with any intent to end their life, but they do not die as a result of their actions (1).”

Statistical Significance

In 2019 during the COVID pandemic, suicide was the tenth leading cause of death among adults (2). Suicide rates have been on the rise since 2000 and were responsible for over 49,000 deaths in 2022. This accounts for one death by suicide every 11 minutes (1). This does not take into account the number of people experiencing suicidal ideation (people who think about suicide) which is an even higher and more alarming statistic. In 2018, 10.7 million American adults seriously thought about suicide, 3.3 million made a plan, and 1.4 million attempted suicide (3). Some vulnerable populations are at a higher risk of suicide, with the highest rates affecting non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native people, non-Hispanic White people, veterans, people who live in rural areas, and workers in certain occupations (ex: mining, healthcare, and construction). Young people who identify as being part of the LGBTQIA+ community also have a higher prevalence of suicidal ideation and attempts compared to those who identify as heterosexual (1).

Suicide and suicide attempts can cause major emotional, physical, and economic impacts on the victim, their families, and communities. People who have attempted suicide and survived may experience serious injuries that can cause them to suffer both physically and mentally, requiring more intensive care for the remainder of their lives. Survivors may also experience lingering depression and other mental health concerns because of their attempt and may be more likely to make an additional attempt in the future (1).

How Can Our Community Help?

No single agency, organization, or community can prevent suicide independently. Preventing suicide requires efforts at all levels of society, including prevention and protective strategies for individuals, families, and communities. All community-based organizations can take an active role in preventing suicide and creating communities where people can thrive (4).

Mental health conditions are a strong predictor of suicide attempts (5). According to the Diagnosed Mental Health Conditions and Risk of Suicide Mortality study performed by Psychiatry Services in 2019, the risk of suicide mortality was highest among individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorder, followed by bipolar disorders, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The risk of suicide death among those with bipolar disorder was higher in women than men (6). At the community health level, treating mental health disorders, improving access and delivery mental health services, providing screenings, and suicide prevention resources in our daily practice is essential.

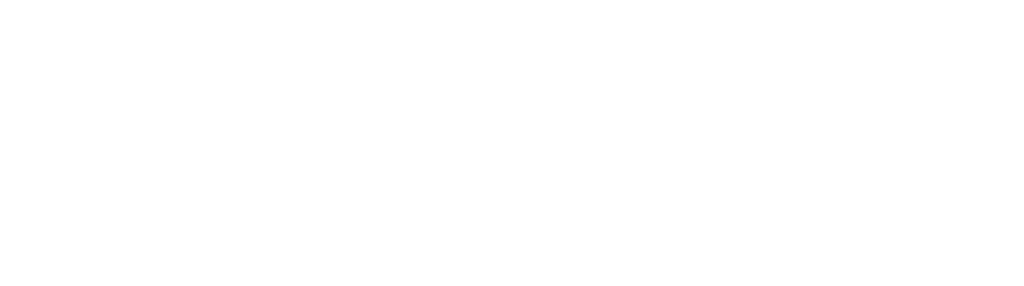

Know the Signs

Warning signs of possible suicidal ideation or planning can look different for everyone, but common signs that can be a cause for concern are:

Screening Tools

Documentation and Coding Tips

If a patient has made a suicide attempt, the following codes can be used to show the additional mental health risk the patient has:

- R45.851 Suicidal Ideations

- T14.91 Suicide Attempt

- Z91.51 Personal History of Suicidal Behavior

Schizophrenia (F20.-)

Schizophrenia is a serious mental health condition that affects how people think, feel and behave. Common symptoms can be a mix of hallucinations, delusions, and disorganized thinking and behavior. People with schizophrenia need lifelong treatment that can include medicine, talk therapy, and learning how to manage daily life activities (7). There is no screening tool widely used or diagnostic test available for schizophrenia and is diagnosed by the characteristic clinical picture.

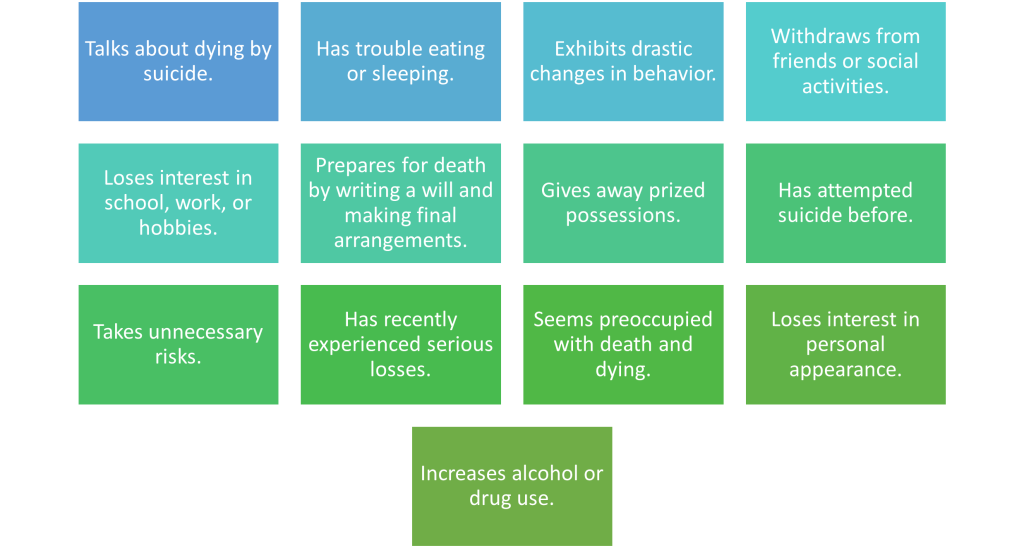

Common Medications

Medicines are the main schizophrenia treatment. Antipsychotic medicines are the most prescribed drugs.

Documentation and Coding Tips

Schizophrenia is a chronic condition that will need constant monitoring and treatment, and therefore should be coded yearly and addressed often when therapeutic management and medication adjustments are made. Documenting schizophrenia in the past medical history section of an encounter in coding language indicates that the condition is resolved and no longer active or receiving treatment. To properly document schizophrenia, the condition should be documented in the active problem list, and when addressed during an office visit should be notated with the patient’s current status and if any symptoms or manifestations have presented themselves.

- F20.0* – Paranoid Schizophrenia

- F20.1* – Disorganized schizophrenia

- F20.2* – Catatonic schizophrenia

- F20.3* – Undifferentiated schizophrenia

- F20.5* – Residual Schizophrenia

- F20.81* – Schizophreniform disorder

- F20.89* – Other schizophrenia

- F20.9* – schizophrenia unspecified

*Code Risk Adjusts in V28 model

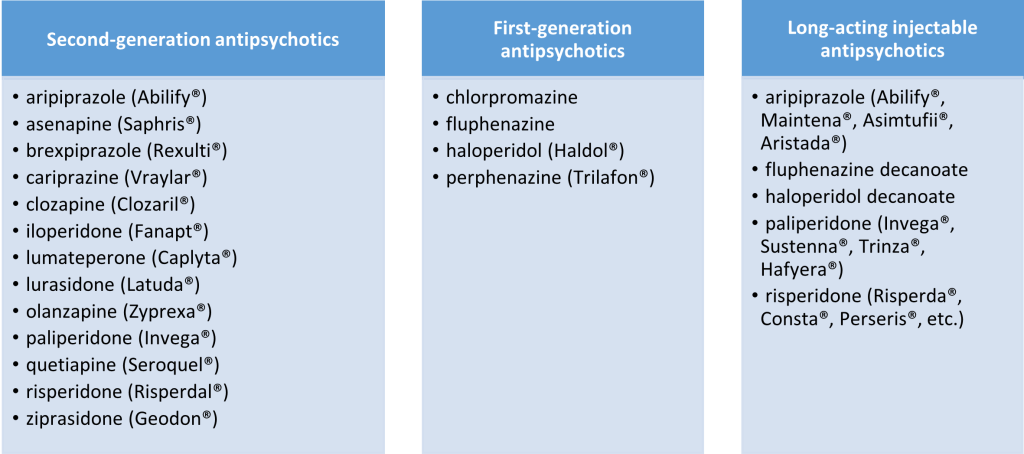

Bipolar Disorder (F31.-)

Bipolar disorder (formerly called manic depression) is a mental health condition that causes extreme mood swings. These mood swings include emotional highs (mania) and lows (depression) (8). The frequency in mood swings can depend on the individual, as mood swings from depression to mania may occur rarely or multiple times a year with a bout usually lasting several days. It is possible for some individuals to have long periods of emotional stability, while others may experience frequent fluctuations in mood swings or experience both depression and mania at the same time. Bipolar disorder is a lifelong condition that is managed by medicines and talk therapy. The following are the DSM V criteria for the different types of bipolar disorder:

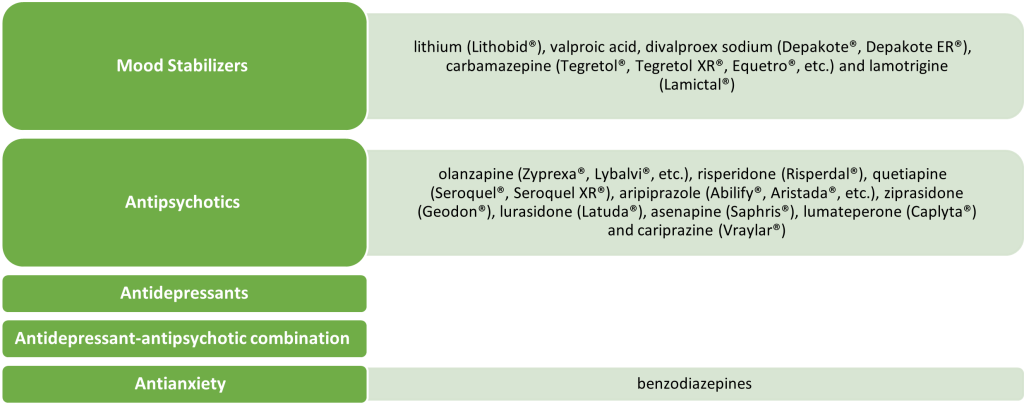

Common Medications

Documentation and Coding Tips

To properly capture the correct code for a patient’s bipolar disorder, the following information should be documented within the medical record:

- Type of bipolar: Bipolar I or Bipolar II

- Current episode: manic, hypomania, depressive, mixed

- Mania is more severe than hypomania, but they have the same symptoms:

- Being much more active, energetic, or agitated than usual.

- Feeling a distorted sense of well-being or too self-confident.

- Needing much less sleep than usual.

- Being unusually talkative and talking fast.

- Having racing thoughts or jumping quickly from one topic to another.

- Being easy to distract.

- Making poor decisions – for example, you may go on buying sprees, take sexual risks, or make foolish investments.

- Depressive episode

- includes symptoms that are severe enough to cause you to have a hard time doing day-to-day activities. An episode includes five or more of these symptoms:

- Having a depressed mood. Feelings of sadness, emptiness, hopelessness or being tearful. Children and teens who are depressed can seem irritable, angry or hostile.

- Having a marked loss of interest or feeling no pleasure in all or most activities.

- Losing a lot of weight when not dieting or overeating and gaining weight. When children don’t gain weight as expected, this can be a sign of depression.

- Sleeping too little or too much.

- Feeling restless or acting slower than usual.

- Being very tired or losing energy.

- Feeling worthless, feeling too guilty or feeling guilty when it’s not necessary.

- Having a hard time thinking or concentrating, or not being able to make decisions.

- Thinking about, planning, or attempting suicide.

- includes symptoms that are severe enough to cause you to have a hard time doing day-to-day activities. An episode includes five or more of these symptoms:

- Mania is more severe than hypomania, but they have the same symptoms:

- The severity of the condition: mild, moderate, severe, in remission

- Presence of psychotic features

It is important to clearly link the medication or therapies being used to treat the patient’s bipolar disorder in the medical record. Do not label bipolar disorder in the past medical history section, even if the patient is stable and has not had a manic or depressive episode for a long time. The condition is chronic and lifelong and should be documented and recoded at least once a year.

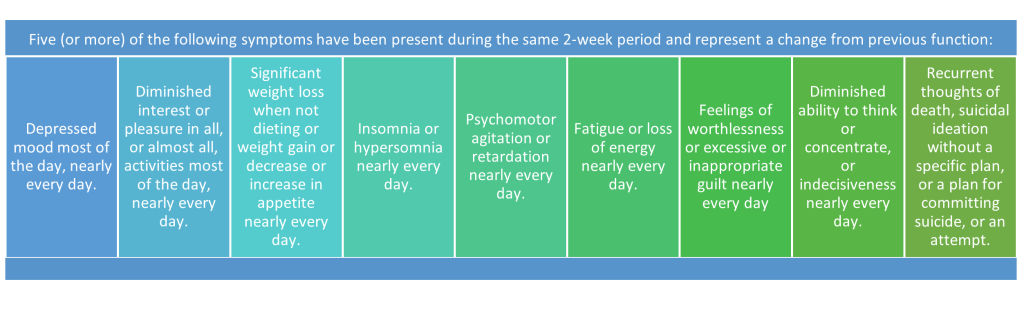

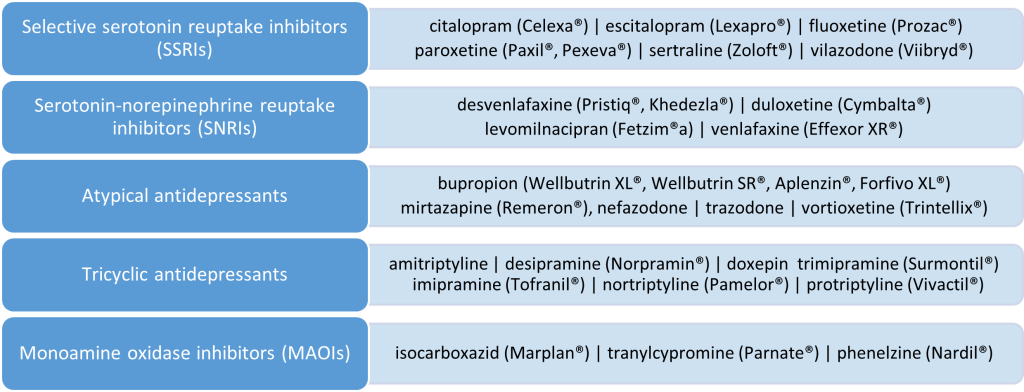

Major Depression (F43)

Major Depressive Disorder (clinical depression) is a mood disorder that causes a continual feeling of sadness and/or loss of interest. Depression affects how you feel, think, and behave and can lead to a variety of emotional, behavioral, and physical problems.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) Criteria

Common Medications

Documentation and Coding Tips

As the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) move from the V24 to the V28 risk adjustment model in 2025, accurately documenting and coding major depression to the highest specificity will be pivotal. It is advised that providers and coders alike review affected patients’ charts to document the current status of depression with as much specificity as possible to ensure the right code is selected for the patient.

Major depressive disorders can be found in code categories F32 and F33. The codes in these categories require fourth and fifth characters to further define the frequency and severity of the condition.

F32 Depressive Episode

- F32.0 – Major depressive disorder, single episode, mild.

- F32.1* – Major depressive disorder, single episode, moderate.

- F32.2* – Major depressive disorder, single episode, severe without psychotic features.

- F32.3* – Major depressive disorder, single episode, severe with psychotic features.

- F32.4 – Major depressive disorder, single episode, in partial remission.

- F32.5 – Major depressive disorder, single episode, in full remission.

- F32.81 – Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

- F32.89 – Other specified depressive episodes.

- F32.9 – Major depressive disorder, single episode, unspecified.

- F32.A – Depression, unspecified.

*Code Risk Adjusts in V28 model

F33 Major Depressive Disorder, Recurrent

- F33.0– Major depressive disorder, recurrent, mild.

- F33.1*- Major depressive disorder, recurrent, moderate.

- F33.2*- Major depressive disorder, recurrent severe without psychotic features.

- F33.3*- Major depressive disorder, recurrent, severe with psychotic symptoms.

- F33.40– Major depressive disorder, recurrent, in remission, unspecified.

- F33.41– Major depressive disorder, recurrent, in partial remission.

- F33.42– Major depressive disorder, recurrent, in full remission.

- F33.8– Other recurrent depressive disorders.

- F33.9– Major depressive disorder, recurrent, unspecified.

*Code Risk Adjusts in V28 model

Screening Codes

- Z13.30 Encounter for screening examination for mental health and behavioral disorders, unspecified

- Z13.31 Encounter for screening for depression

- Z13.39 Encounter for screening examination for other mental health and behavioral disorders

- Behavioral Health Screening (G0444) and include results: (HCPCS CODES)

- G8431 – positive depression screening/follow-up plan documented

- G8510 – negative depression screening

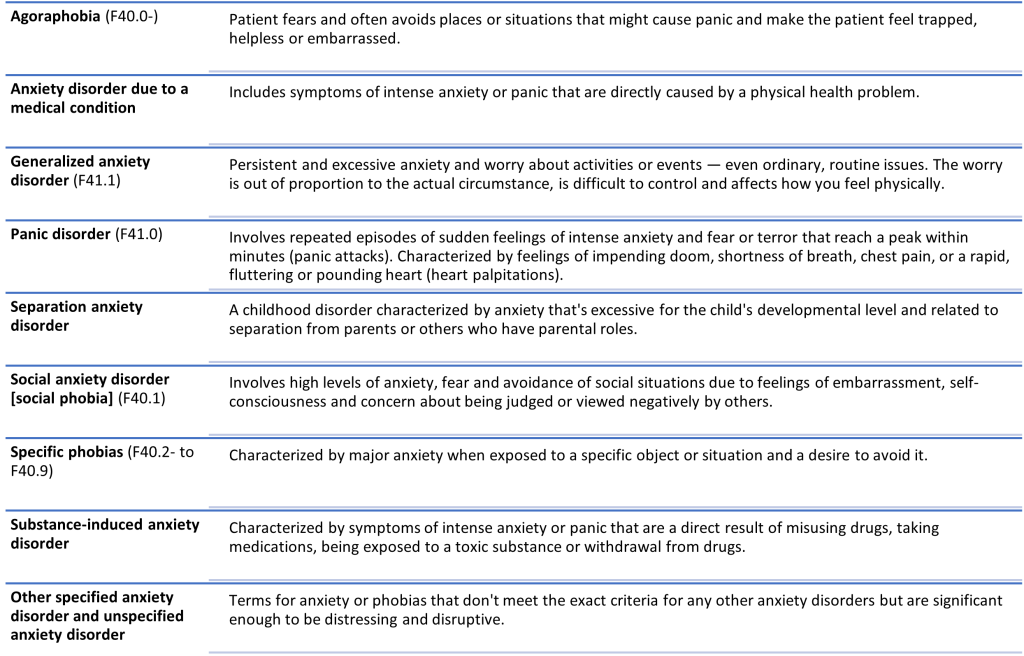

Anxiety Disorders (F40.-)

While many individuals experience anxiety symptoms within their lifetime, anxiety disorders are characterized by intense, excessive and persistent worry and fear about everyday situations. These disorders involve repeated episodes of sudden feelings of intense anxiety and fear or terror, to the point where the fear can interfere with daily activities (10). Examples of anxiety disorders include generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder (social phobia), specific phobias and separation anxiety disorder. A patient can also present with more than one anxiety disorder at any given time.

Types of Anxiety Disorders

Documentation and Coding Tips

Anxiety related ICD-10-CM codes do not risk adjust in the V28 model, however the clinical and societal impact these conditions have led us to stress the importance of documenting these codes even in the absence of additional RAF weight. When coding for anxiety disorders, specificity is needed to determine the type of anxiety disorder present, the current status or the patient’s anxiety, and a treatment plan of the anxiety. Linking the anxiety to the medication(s) or therapy(ies) being used to treat the condition is important to show that the condition is being actively treated. A stable anxiety disorder that is being actively treated by medications is still considered an active condition and should be documented and coded as such.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD] (F90)

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a chronic yet very common neurodevelopment disorder that affects millions of children and adults. ADHD includes a combination of persistent problems, such as difficulties with attention, hyperactivity, and impulsive behavior (12). Males are more commonly diagnosed, as women present differently than their male counterparts. Women are at higher risk for self-harm than men, apart from completed suicides which are higher in males (13). There are three main subtypes of ADHD:

- Predominantly inattentive: the patients’ symptoms fall under inattention.

- Predominantly hyperactive/impulsive: the majority of the patients’ symptoms are hyperactive and impulsive.

- Combined: this is a mix of inattentive symptoms and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms.

ADHD can be a lifelong challenge for both children and adults. Children with ADHD often struggle in academic settings and face judgment from peers and adult figures. Adults with ADHD may have trouble following directions, remembering information, concentrating and/or organizing tasks. ADHD patients tend to have more accidents and injuries, have poor self-esteem, are more likely to have trouble interacting and feeling accepted by peers, and are at increased risk of alcohol, drug abuse, and other reckless behavior (12).

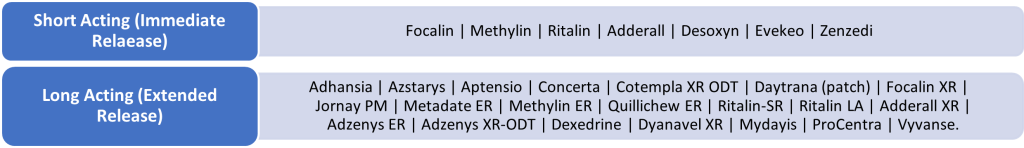

Common Medications

Documentation and Coding Tips

ADHD related ICD-10-CM codes do not risk adjust in the V28 model, however with the high correlation between ADHD and suicide, it is important to address all the same. To code for ADHD appropriately, the type of ADHD should be documented in the medical record, along with any comorbidities associated with ADHD, and the medication(s) and/or therapy(ies) being used for management. Do not label ADHD in the past medical history section, even if the patient Is stable. The condition is chronic and lifelong and should be documented and recoded at least once a year. Patients with ADHD are more likely than others to also have comorbid conditions such as:

- Oppositional defiant disorder [ODD] (F91.3): a pattern of negative, defiant, and hostile behavior toward authority figures.

- Conduct disorder (F91.-): antisocial behavior such as stealing, fighting, destroying property, and harming people or animals.

- Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder: irritability and problems tolerating frustration.

- Learning disabilities: including problems with reading, writing, understanding and communicating.

- Substance use disorders: including drugs (F11.- to F16.-), alcohol (F10.-), and smoking (F17.-).

- Anxiety disorders (F40.- to F41.-)

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) (F42.-)

- Depression (F32.-), bipolar disorder (F31.-), and other disorders

- Autism spectrum disorder: a condition related to brain development that impacts how a person perceives and socializes with others.

- Tic disorder or Tourette syndrome (F95.-): disorders that involve repetitive movements or unwanted sounds (tics) that can’t be easily controlled.

If a friend, colleague, patient, or loved one is in danger of self-harm or suicide, know there is still hope for a better tomorrow.

Call or text 988 for the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline – Call. Text. Chat. (988lifeline.org)

Sources

- Facts About Suicide | CDC

- Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among Adults Aged ≥18 Years — United States, 2015–2019 | MMWR (cdc.gov)

- Suicide Prevention | Office of Policy, Performance, and Evaluation (cdc.gov)

- Community-Based Suicide Prevention – National Strategy for Suicide Prevention | NCBI Bookshelf (nih.gov)

- Mental Disorders, Comorbidity and Suicidal Behavior: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication | PMC (nih.gov)

- Diagnosed Mental Health Conditions and Risk of Suicide Mortality |PMC (nih.gov)

- Schizophrenia – Symptoms and causes | Mayo Clinic

- Bipolar Disorder – Symptoms and causes | Mayo Clinic

- Bipolar Disorders Adult Guidelines 2019-2020 | (floridabhcenter.org)

- Anxiety Disorders – Symptoms and Causes | Mayo Clinic

- Anxiety Disorders – Diagnosis and Treatment | Mayo Clinic

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children – Symptoms and causes | Mayo Clinic

- ADHD, Self-Harm, and Suicide | CHADD